Oregon Country on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Oregon Country was a large region of the

The Oregon Country was originally claimed by Great Britain, France, Russia, and Spain; the Spanish claim was later taken up by the United States. The extent of the region being claimed was vague at first, evolving over decades into the specific borders specified in the U.S.-British treaty of 1818. The United States based its claim in part on Robert Gray's entry of the Columbia River in 1792 and the Lewis and Clark Expedition. Great Britain based its claim in part on British overland explorations of the Columbia River by David Thompson and on prior discovery and exploration along the coast. Spain's claim was based on the

The Oregon Country was originally claimed by Great Britain, France, Russia, and Spain; the Spanish claim was later taken up by the United States. The extent of the region being claimed was vague at first, evolving over decades into the specific borders specified in the U.S.-British treaty of 1818. The United States based its claim in part on Robert Gray's entry of the Columbia River in 1792 and the Lewis and Clark Expedition. Great Britain based its claim in part on British overland explorations of the Columbia River by David Thompson and on prior discovery and exploration along the coast. Spain's claim was based on the

In 1805, the American Lewis and Clark Expedition marked the first official American exploration of the area, creating the first temporary settlement of Euro-Americans in the area near the mouth of the Columbia River at

In 1805, the American Lewis and Clark Expedition marked the first official American exploration of the area, creating the first temporary settlement of Euro-Americans in the area near the mouth of the Columbia River at

In 1843, settlers in the Willamette Valley established a provisional government at Champoeg. Political pressure in the United States urged the occupation of all the Oregon Country. Expansionists in the American South wanted to annex Texas, while their counterparts in the northeast wanted to annex the Oregon Country. It was seen as significant that the expansions be parallel, as the relative proximity to other states and territories made it appear likely that Texas would be pro-slavery and Oregon against slavery.

In the 1844 U.S. Presidential election, the Democrats had called for expansion into both areas. After his election as president, however,

In 1843, settlers in the Willamette Valley established a provisional government at Champoeg. Political pressure in the United States urged the occupation of all the Oregon Country. Expansionists in the American South wanted to annex Texas, while their counterparts in the northeast wanted to annex the Oregon Country. It was seen as significant that the expansions be parallel, as the relative proximity to other states and territories made it appear likely that Texas would be pro-slavery and Oregon against slavery.

In the 1844 U.S. Presidential election, the Democrats had called for expansion into both areas. After his election as president, however,

Chronology of Oregon Events

(Treaty of St. Petersburg, 1825) {{Coord, 48, -122, region:US-OR_dim:1800000, display=title

Pacific Northwest

The Pacific Northwest (sometimes Cascadia, or simply abbreviated as PNW) is a geographic region in western North America bounded by its coastal waters of the Pacific Ocean to the west and, loosely, by the Rocky Mountains to the east. Though ...

of North America

North America is a continent in the Northern Hemisphere and almost entirely within the Western Hemisphere. It is bordered to the north by the Arctic Ocean, to the east by the Atlantic Ocean, to the southeast by South America and the Car ...

that was subject to a long dispute between the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

and the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

in the early 19th century. The area, which had been created by the Treaty of 1818

The Convention respecting fisheries, boundary and the restoration of slaves, also known as the London Convention, Anglo-American Convention of 1818, Convention of 1818, or simply the Treaty of 1818, is an international treaty signed in 1818 betw ...

, consisted of the land north of 42°N latitude, south of 54°40′N latitude, and west of the Rocky Mountains

The Rocky Mountains, also known as the Rockies, are a major mountain range and the largest mountain system in North America. The Rocky Mountains stretch in straight-line distance from the northernmost part of western Canada, to New Mexico in ...

down to the Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the continen ...

and east to the Continental Divide

A continental divide is a drainage divide on a continent such that the drainage basin on one side of the divide feeds into one ocean or sea, and the basin on the other side either feeds into a different ocean or sea, or else is endorheic, not ...

. Article III of the 1818 treaty gave joint control to both nations for ten years, allowed land to be claimed, and guaranteed free navigation to all mercantile trade. However, both countries disputed the terms of the international treaty. Oregon Country was the American name while the British used Columbia District

The Columbia District was a fur trading district in the Pacific Northwest region of British North America in the 19th century. Much of its territory overlapped with the disputed Oregon Country. It was explored by the North West Company betw ...

for the region

In geography, regions, otherwise referred to as zones, lands or territories, are areas that are broadly divided by physical characteristics (physical geography), human impact characteristics (human geography), and the interaction of humanity and t ...

.

British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

and French Canadian

Canadians (french: Canadiens) are people identified with the country of Canada. This connection may be residential, legal, historical or cultural. For most Canadians, many (or all) of these connections exist and are collectively the source of ...

fur traders

The fur trade is a worldwide industry dealing in the acquisition and sale of animal fur. Since the establishment of a world fur market in the early modern period, furs of boreal, polar and cold temperate mammalian animals have been the mo ...

had entered Oregon Country prior to 1810 before the arrival of American settlers from the mid-1830s onwards, which led to the foundation of the Provisional Government of Oregon

The Provisional Government of Oregon was a popularly elected settler government created in the Oregon Country, in the Pacific Northwest region of North America. Its formation had been advanced at the Champoeg Meetings since February 17, 1841, ...

. Its coastal areas north from the Columbia River

The Columbia River (Upper Chinook: ' or '; Sahaptin: ''Nch’i-Wàna'' or ''Nchi wana''; Sinixt dialect'' '') is the largest river in the Pacific Northwest region of North America. The river rises in the Rocky Mountains of British Columbia, C ...

were frequented by ships from all nations engaged in the maritime fur trade

The maritime fur trade was a ship-based fur trade system that focused on acquiring furs of sea otters and other animals from the indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast and natives of Alaska. The furs were mostly sold in China in ex ...

, with many vessels between the 1790s and 1810s coming from Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

. The Hudson's Bay Company

The Hudson's Bay Company (HBC; french: Compagnie de la Baie d'Hudson) is a Canadian retail business group. A fur trading business for much of its existence, HBC now owns and operates retail stores in Canada. The company's namesake business div ...

, whose Columbia Department comprised most of the Oregon Country and north into New Caledonia

)

, anthem = ""

, image_map = New Caledonia on the globe (small islands magnified) (Polynesia centered).svg

, map_alt = Location of New Caledonia

, map_caption = Location of New Caledonia

, mapsize = 290px

, subdivision_type = Sovereign st ...

and beyond 54°40′N, with operations reaching tributaries of the Yukon River

The Yukon River (Gwichʼin language, Gwich'in: ''Ųųg Han'' or ''Yuk Han'', Central Alaskan Yup'ik language, Yup'ik: ''Kuigpak'', Inupiaq language, Inupiaq: ''Kuukpak'', Deg Xinag language, Deg Xinag: ''Yeqin'', Hän language, Hän: ''Tth'echù' ...

, managed and represented British interests in the region.

After the dispute became an election issue in the US presidential elections of 1844, the United Kingdom and the United States agreed to settle the problem with the Oregon Treaty

The Oregon Treaty is a treaty between the United Kingdom and the United States that was signed on June 15, 1846, in Washington, D.C. The treaty brought an end to the Oregon boundary dispute by settling competing American and British claims to t ...

in 1846. It established the British-American boundary at the 49th parallel (except Vancouver Island

Vancouver Island is an island in the northeastern Pacific Ocean and part of the Canadian Provinces and territories of Canada, province of British Columbia. The island is in length, in width at its widest point, and in total area, while are o ...

). With the end of joint occupancy, the region south of the 49th parallel became Oregon Territory in the United States while the northern portion became part of the British colonies of British Columbia

British Columbia (commonly abbreviated as BC) is the westernmost province of Canada, situated between the Pacific Ocean and the Rocky Mountains. It has a diverse geography, with rugged landscapes that include rocky coastlines, sandy beaches, ...

and Vancouver Island

Vancouver Island is an island in the northeastern Pacific Ocean and part of the Canadian Provinces and territories of Canada, province of British Columbia. The island is in length, in width at its widest point, and in total area, while are o ...

. The area which once encompassed Oregon Country now lies within the present-day borders of the Canadian province

Within the geographical areas of Canada, the ten provinces and three territories are sub-national administrative divisions under the jurisdiction of the Canadian Constitution. In the 1867 Canadian Confederation, three provinces of British North ...

of British Columbia

British Columbia (commonly abbreviated as BC) is the westernmost province of Canada, situated between the Pacific Ocean and the Rocky Mountains. It has a diverse geography, with rugged landscapes that include rocky coastlines, sandy beaches, ...

and all of the U.S. state

In the United States, a state is a constituent political entity, of which there are 50. Bound together in a political union, each state holds governmental jurisdiction over a separate and defined geographic territory where it shares its sove ...

s of Oregon

Oregon () is a U.S. state, state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. The Columbia River delineates much of Oregon's northern boundary with Washington (state), Washington, while the Snake River delineates much of it ...

, Washington

Washington commonly refers to:

* Washington (state), United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A metonym for the federal government of the United States

** Washington metropolitan area, the metropolitan area centered o ...

, and Idaho

Idaho ( ) is a state in the Pacific Northwest region of the Western United States. To the north, it shares a small portion of the Canada–United States border with the province of British Columbia. It borders the states of Montana and Wyom ...

, as well as parts of Montana

Montana () is a state in the Mountain West division of the Western United States. It is bordered by Idaho to the west, North Dakota and South Dakota to the east, Wyoming to the south, and the Canadian provinces of Alberta, British Columbi ...

and Wyoming

Wyoming () is a U.S. state, state in the Mountain states, Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. It is bordered by Montana to the north and northwest, South Dakota and Nebraska to the east, Idaho to the west, Utah to the south ...

.

Toponym

The earliest evidence of the name "Oregon" has Spanish origins. The term comes from the historical chronicle (1598) which was written by the New Spaniard Rodrigo Motezuma and which made reference to the Columbia River when the Spanish explorers penetrated into the North American territory that became part of theViceroyalty of New Spain

New Spain, officially the Viceroyalty of New Spain ( es, Virreinato de Nueva España, ), or Kingdom of New Spain, was an integral territorial entity of the Spanish Empire, established by Habsburg Spain during the Spanish colonization of the Amer ...

. This chronicle is the first topographical and linguistic source with respect to the place name ''Oregon''. There are also two other sources with Spanish origins such as the name ''Oregano'', which grows in the southern part of the region. It is most probable that the American territory was named by the Spaniards, as there are some populations in Spain such as "Arroyo del Oregón", which is in the province of Ciudad Real, also considering that the individualization in Spanish language with the mutation of the letter ''g'' instead of ''j''.

Another theory is that French Canadian fur company employees called the Columbia River "hurricane river" , because of the strong winds of the Columbia Gorge

The Columbia River Gorge is a canyon of the Columbia River in the Pacific Northwest of the United States. Up to deep, the canyon stretches for over as the river winds westward through the Cascade Range, forming the boundary between the sta ...

. George R. Stewart

George Rippey Stewart (May 31, 1895 – August 22, 1980) was an American historian, toponymist, novelist, and a professor of English at the University of California, Berkeley. His 1959 book, ''Pickett's Charge'', a detailed history of the final ...

argues in a 1944 article in ''American Speech'' that the name came from an engraver's error in a French map published in the early 18th century, on which the ''Ouisiconsink'' (Wisconsin River

The Wisconsin River is a tributary of the Mississippi River in the U.S. state of Wisconsin. At approximately 430 miles (692 km) long, it is the state's longest river. The river's name, first recorded in 1673 by Jacques Marquette as "Meskousi ...

) was spelled "Ouaricon-sint", broken on two lines with the -sint below, so that there appeared to be a river flowing to the west named "Ouaricon". This theory was endorsed in ''Oregon Geographic Names

''Oregon Geographic Names'' is a compilation of the origin and meaning of place names in the U.S. state of Oregon, published by the Oregon Historical Society. The book was originally published in 1928. It was compiled and edited by Lewis A. McArth ...

'' as "the most plausible explanation".

Early exploration

George Vancouver exploredPuget Sound

Puget Sound ( ) is a sound of the Pacific Northwest, an inlet of the Pacific Ocean, and part of the Salish Sea. It is located along the northwestern coast of the U.S. state of Washington. It is a complex estuarine system of interconnected ma ...

in 1792. Vancouver claimed it for Great Britain on 4 June 1792, naming it for one of his officers, Lieutenant Peter Puget. Alexander Mackenzie was the first European to cross North America by land north of New Spain, arriving at Bella Coola on what is now the central coast of British Columbia

, settlement_type = Region of British Columbia

, image_skyline =

, nickname = "The Coast"

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Canada

, subdivision_type1 = Province

, subdivision_name1 = British ...

in 1793. From 1805 to 1806 Meriwether Lewis

Meriwether Lewis (August 18, 1774 – October 11, 1809) was an American explorer, soldier, politician, and public administrator, best known for his role as the leader of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, also known as the Corps of Discovery, with ...

and William Clark

William Clark (August 1, 1770 – September 1, 1838) was an American explorer, soldier, Indian agent, and territorial governor. A native of Virginia, he grew up in pre-statehood Kentucky before later settling in what became the state of Misso ...

explored the territory for the United States on the Lewis and Clark Expedition

The Lewis and Clark Expedition, also known as the Corps of Discovery Expedition, was the United States expedition to cross the newly acquired western portion of the country after the Louisiana Purchase. The Corps of Discovery was a select gro ...

.

David Thompson, working for the Montreal

Montreal ( ; officially Montréal, ) is the List of the largest municipalities in Canada by population, second-most populous city in Canada and List of towns in Quebec, most populous city in the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian ...

-based North West Company

The North West Company was a fur trading business headquartered in Montreal from 1779 to 1821. It competed with increasing success against the Hudson's Bay Company in what is present-day Western Canada and Northwestern Ontario. With great weal ...

, explored much of the region beginning in 1807, with his friend and colleague Simon Fraser, following the Fraser River to its mouth in 1808, attempting to ascertain whether it was the Columbia, as had been theorized about its northern reaches through New Caledonia, where it was known by its Dakleh name as the "Tacoutche Tesse". Thompson was the first European to voyage down the entire length of Columbia River. Along the way, his party camped at the junction with the Snake River

The Snake River is a major river of the greater Pacific Northwest region in the United States. At long, it is the largest tributary of the Columbia River, in turn, the largest North American river that empties into the Pacific Ocean. The Snake ...

on 9 July 1811. He erected a pole and a notice claiming the country for the United Kingdom and stating the intention of the North West Company to build a trading post on the site. Later in 1811, on the same expedition, he finished his survey of the entire Columbia, arriving at a partially constructed Fort Astoria

Fort Astoria (also named Fort George) was the primary fur trading post of John Jacob Astor's Pacific Fur Company (PFC). A maritime contingent of PFC staff was sent on board the ''Tonquin (1807 ship), Tonquin'', while another party traveled overl ...

two months after the departure of John Jacob Astor

John Jacob Astor (born Johann Jakob Astor; July 17, 1763 – March 29, 1848) was a German-American businessman, merchant, real estate mogul, and investor who made his fortune mainly in a fur trade monopoly, by History of opium in China, smuggl ...

's ill-fated '' Tonquin''.

Territorial evolution

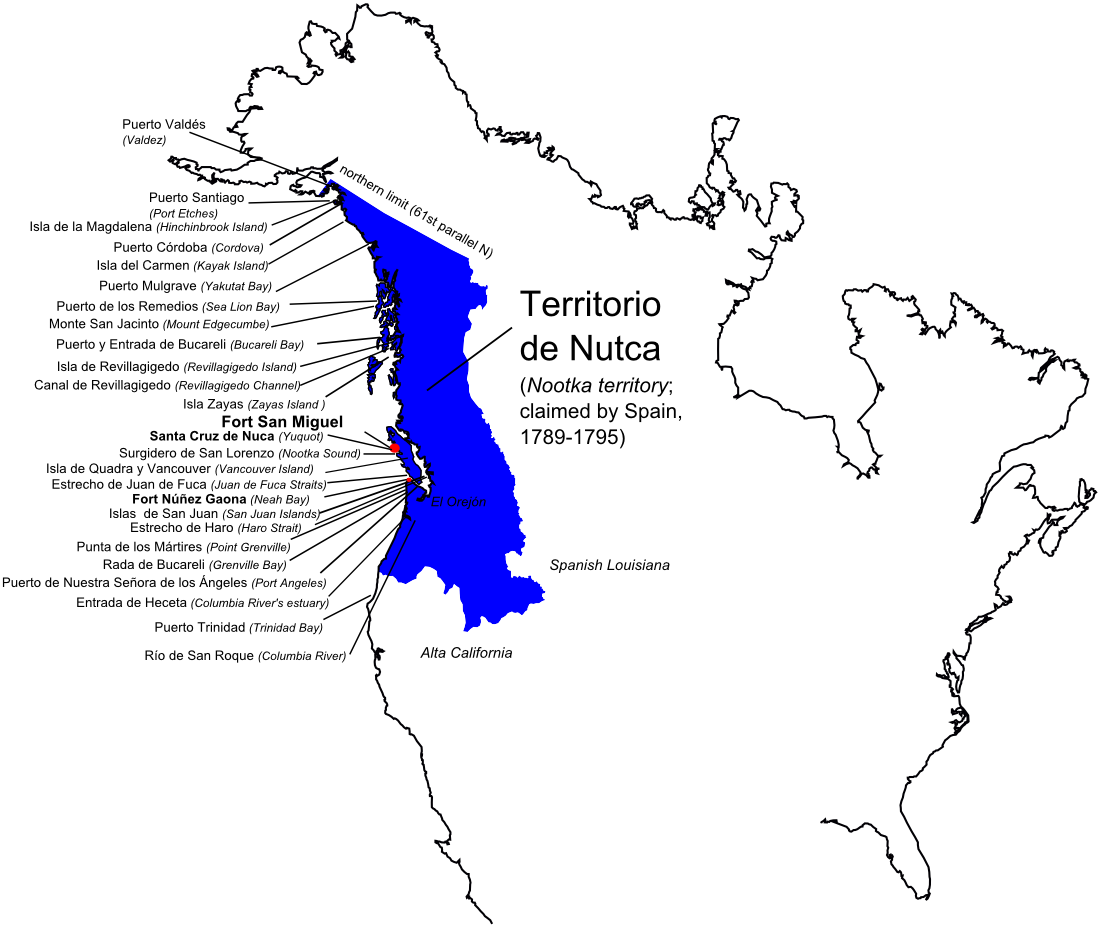

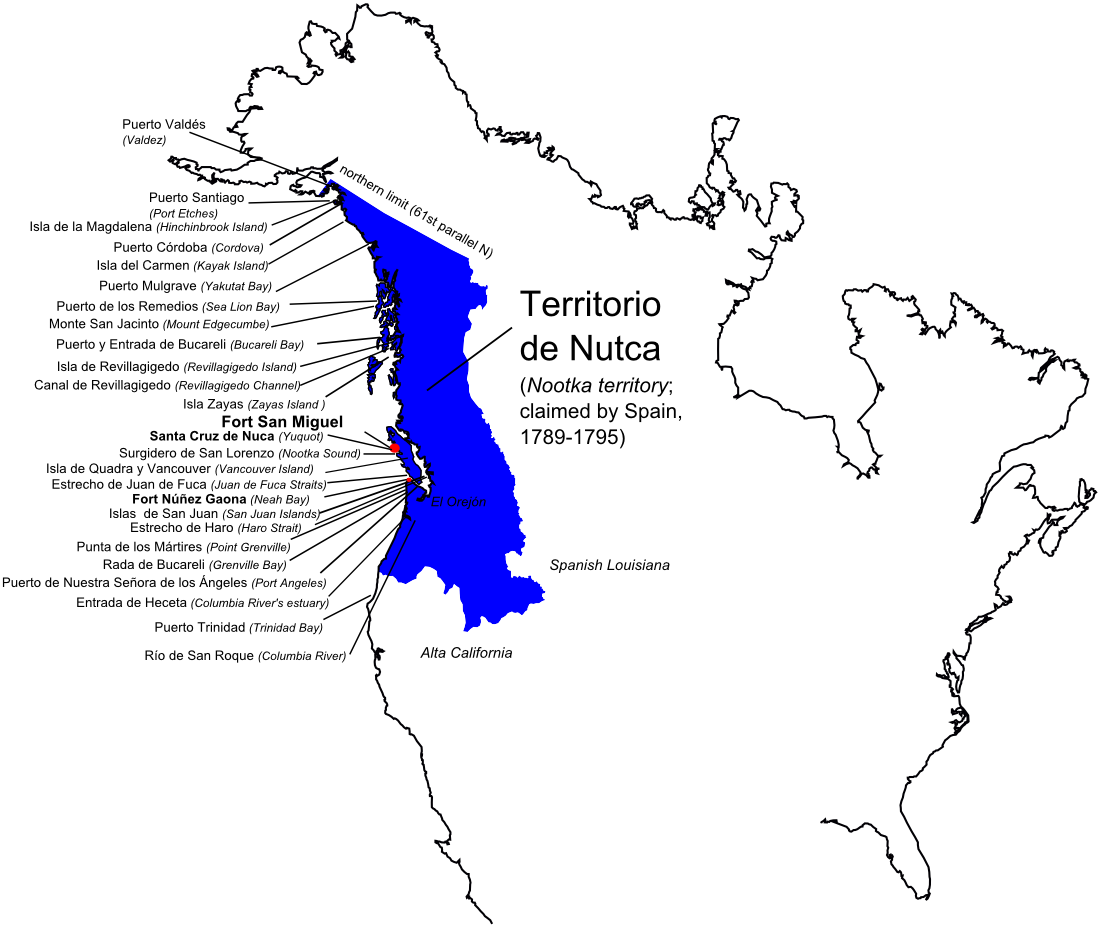

The Oregon Country was originally claimed by Great Britain, France, Russia, and Spain; the Spanish claim was later taken up by the United States. The extent of the region being claimed was vague at first, evolving over decades into the specific borders specified in the U.S.-British treaty of 1818. The United States based its claim in part on Robert Gray's entry of the Columbia River in 1792 and the Lewis and Clark Expedition. Great Britain based its claim in part on British overland explorations of the Columbia River by David Thompson and on prior discovery and exploration along the coast. Spain's claim was based on the

The Oregon Country was originally claimed by Great Britain, France, Russia, and Spain; the Spanish claim was later taken up by the United States. The extent of the region being claimed was vague at first, evolving over decades into the specific borders specified in the U.S.-British treaty of 1818. The United States based its claim in part on Robert Gray's entry of the Columbia River in 1792 and the Lewis and Clark Expedition. Great Britain based its claim in part on British overland explorations of the Columbia River by David Thompson and on prior discovery and exploration along the coast. Spain's claim was based on the Inter caetera

''Inter caetera'' ('Among other orks) was a papal bull issued by Pope Alexander VI on the 4 May () 1493, which granted to the Catholic Monarchs King Ferdinand II of Aragon and Queen Isabella I of Castile all lands to the "west and south" of ...

and Treaty of Tordesillas

The Treaty of Tordesillas, ; pt, Tratado de Tordesilhas . signed in Tordesillas, Spain on 7 June 1494, and authenticated in Setúbal, Portugal, divided the newly discovered lands outside Europe between the Portuguese Empire and the Spanish Emp ...

of 1493–94, as well as explorations of the Pacific coast in the late 18th century. Russia based its claim on its explorations and trading activities in the region and asserted its ownership of the region north of the 51st parallel by the Ukase of 1821

The Ukase of 1821 (russian: Указ 1821 года) was a Russian proclamation (a ''ukase'') of territorial sovereignty over northwestern North America, roughly present-day Alaska and most of the Pacific Northwest. The ''ukase'' was declared on Se ...

, which was quickly challenged by the other powers and withdrawn to 54°40′N by separate treaties with the U.S. and Britain in 1824 and 1825 respectively.

Spain gave up its claims of exclusivity via the Nootka Convention

The Nootka Sound Conventions were a series of three agreements between the Kingdom of Spain and the Kingdom of Great Britain, signed in the 1790s, which averted a war between the two countries over overlapping claims to portions of the Pacific No ...

s of the 1790s. In the Nootka Conventions, which followed the Nootka Crisis

The Nootka Crisis, also known as the Spanish Armament, was an international incident and political dispute between the Nuu-chah-nulth Nation, the Spanish Empire, the Kingdom of Great Britain, and the fledgling United States of America triggered b ...

, Spain granted Britain rights to the Pacific Northwest, although it did not establish a northern boundary for Spanish California, nor did it extinguish Spanish rights to the Pacific Northwest. Spain later relinquished any remaining claims to territory north of the 42nd parallel to the United States as part of the Adams-Onís Treaty of 1819. In the 1820s, Russia gave up its claims south of 54°40′ and east of the 141st meridian in separate treaties with the United States and Britain.

Meanwhile, the United States and Britain negotiated the Anglo-American Convention of 1818, which extended the boundary between their territories west along the 49th parallel to the Rocky Mountains. The two countries agreed to "joint occupancy" of the land west of the Rockies to the Pacific Ocean.

In 1843, settlers established their own government, called the Provisional Government of Oregon

The Provisional Government of Oregon was a popularly elected settler government created in the Oregon Country, in the Pacific Northwest region of North America. Its formation had been advanced at the Champoeg Meetings since February 17, 1841, ...

. A legislative committee drafted a code of laws known as the Organic Law. It included the creation of an executive committee of three, a judiciary, militia, land laws, and four counties. There was vagueness and confusion over the nature of the 1843 Organic Law, in particular whether it was constitutional

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When these princip ...

or statutory

A statute is a formal written enactment of a legislative authority that governs the legal entities of a city, state, or country by way of consent. Typically, statutes command or prohibit something, or declare policy. Statutes are rules made by le ...

. In 1844, a new legislative committee decided to consider it statutory. The 1845 Organic Law made additional changes, including allowing the participation of British subject

The term "British subject" has several different meanings depending on the time period. Before 1949, it referred to almost all subjects of the British Empire (including the United Kingdom, Dominions, and colonies, but excluding protectorates ...

s in the government. Although the Oregon Treaty of 1846 settled the boundaries of U.S. jurisdiction, the provisional government continued to function until 1849, when the first governor of Oregon Territory

The Territory of Oregon was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from August 14, 1848, until February 14, 1859, when the southwestern portion of the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Oregon. Ori ...

arrived. A faction of Oregon politicians hoped to continue Oregon's political evolution into an independent nation, but the pressure to join the United States prevailed by 1848, four months after the Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed the 1 ...

.

Early settlement

In 1805, the American Lewis and Clark Expedition marked the first official American exploration of the area, creating the first temporary settlement of Euro-Americans in the area near the mouth of the Columbia River at

In 1805, the American Lewis and Clark Expedition marked the first official American exploration of the area, creating the first temporary settlement of Euro-Americans in the area near the mouth of the Columbia River at Fort Clatsop

Fort Clatsop was the encampment of the Lewis and Clark Expedition in the Oregon Country near the mouth of the Columbia River during the winter of 1805–1806. Located along the Lewis and Clark River at the north end of the Clatsop Plains approxi ...

. Two years later in 1807, David Thompson of the Montreal-based North West Company penetrated the Oregon Country from the north, via Athabasca Pass

Athabasca Pass (el. ) is a high mountain pass in the Canadian Rockies on the border between Alberta and British Columbia. In fur trade days it connected Jasper House on the Athabasca River with Boat Encampment on the Columbia River.Whittaker, Jo ...

, near the headwaters of the Columbia River. From there he navigated nearly the full length of the river through to the Pacific Ocean.

In 1810, John Jacob Astor commissioned and began the construction of the American Pacific Fur Company

The Pacific Fur Company (PFC) was an American fur trade venture wholly owned and funded by John Jacob Astor that functioned from 1810 to 1813. It was based in the Pacific Northwest, an area contested over the decades between the United Kingdom o ...

fur-trading post at Fort Astoria, just from the site of Lewis and Clark's former Fort Clatsop, completing construction of the first permanent Euro-American settlement in the area in 1811. This settlement later served as the nucleus of present day Astoria, Oregon. During the period of the construction of Fort Astoria, Thompson traveled down the Columbia River, noting the partially constructed American Fort Astoria only two months after the departure of the supply ship ''Tonquin''.

Along the way, Thompson had set foot on and claimed for the British Crown, the lands in the vicinity of the future Fort Nez Percés

Fort Nez Percés (or Fort Nez Percé, with or without the accent aigu), later known as (Old) Fort Walla Walla, was a fortified fur trading post on the Columbia River on the territory of modern-day Wallula, Washington. Despite being named after th ...

site at the confluence of the Columbia and Snake rivers. This claim initiated a very brief era of competition between American and British fur traders. During the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It bega ...

, Fort Astoria was captured by the British and sold to the North West Company. Under British control, Fort Astoria was renamed Fort George.

In 1821 when the North West Company was merged with the Hudson's Bay Company, the British Parliament moved to impose the laws of Upper Canada upon British subjects in Columbia District

The Columbia District was a fur trading district in the Pacific Northwest region of British North America in the 19th century. Much of its territory overlapped with the disputed Oregon Country. It was explored by the North West Company betw ...

and Rupert's Land

Rupert's Land (french: Terre de Rupert), or Prince Rupert's Land (french: Terre du Prince Rupert, link=no), was a territory in British North America which comprised the Hudson Bay drainage basin; this was further extended from Rupert's Land t ...

, and issued the authority to enforce those laws to the Hudson's Bay Company. Chief Factor

A factor is a type of trader who receives and sells goods on commission, called factorage. A factor is a mercantile fiduciary transacting business in his own name and not disclosing his principal. A factor differs from a commission merchant in ...

John McLoughlin was appointed manager of the district's operations in 1824. He moved the regional company headquarters to Fort Vancouver

Fort Vancouver was a 19th century fur trading post that was the headquarters of the Hudson's Bay Company's Columbia Department, located in the Pacific Northwest. Named for Captain George Vancouver, the fort was located on the northern bank of th ...

(modern Vancouver, Washington

Vancouver is a city on the north bank of the Columbia River in the U.S. state of Washington, located in Clark County. Incorporated in 1857, Vancouver has a population of 190,915 as of the 2020 census, making it the fourth-largest city in Was ...

) in 1824. Fort Vancouver became the centre of a thriving colony of mixed origin, including Scottish Canadians

Scottish Canadians are people of Scottish descent or heritage living in Canada. As the third-largest ethnic group in Canada and amongst the first Europeans to settle in the country, Scottish people have made a large impact on Canadian culture sin ...

and Scots, English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ide ...

, French Canadians, Hawaiians

Native Hawaiians (also known as Indigenous Hawaiians, Kānaka Maoli, Aboriginal Hawaiians, First Hawaiians, or simply Hawaiians) ( haw, kānaka, , , and ), are the indigenous ethnic group of Polynesian people of the Hawaiian Islands.

Hawaii ...

, Algonkians, and Iroquois

The Iroquois ( or ), officially the Haudenosaunee ( meaning "people of the longhouse"), are an Iroquoian-speaking confederacy of First Nations peoples in northeast North America/ Turtle Island. They were known during the colonial years to ...

, as well as the offspring of company employees who had intermarried with various local native populations.

Astor continued to compete for Oregon Country furs through his American Fur Company operations in the Rockies. In the 1820s, a few American explorers and traders visited this land beyond the Rocky Mountains. Long after the Lewis and Clark Expedition and also after the consolidation of the fur trade in the region by the Canadian fur companies, American mountain men

A mountain man is an explorer who lives in the wilderness. Mountain men were most common in the North American Rocky Mountains from about 1810 through to the 1880s (with a peak population in the early 1840s). They were instrumental in opening up ...

such as Jedediah Smith and Jim Beckwourth came roaming into and across the Rocky Mountains, following Indian trails through the Rockies to California and Oregon. They sought beaver

Beavers are large, semiaquatic rodents in the genus ''Castor'' native to the temperate Northern Hemisphere. There are two extant species: the North American beaver (''Castor canadensis'') and the Eurasian beaver (''C. fiber''). Beavers ar ...

pelts and other furs, which were obtained by trapping

Animal trapping, or simply trapping or gin, is the use of a device to remotely catch an animal. Animals may be trapped for a variety of purposes, including food, the fur trade, hunting, pest control, and wildlife management.

History

Neolithic ...

. These were difficult to obtain in the Oregon Country because of the Hudson's Bay Company policy of creating a "fur desert": deliberate over-hunting of the area's frontiers, so that American trades would find nothing there. The mountain men, like the Metis

Metis or Métis may refer to:

Ethnic groups

* Métis, recognized Indigenous communities in Canada and America whose distinct culture and language emerged after early intermarriage between First Nations peoples and early European settlers, prima ...

employees of the Canadian fur companies, adopted Indian ways, and many of them married Native American women.

Reports of Oregon Country eventually circulated in the eastern United States

The Eastern United States, commonly referred to as the American East, Eastern America, or simply the East, is the region of the United States to the east of the Mississippi River. In some cases the term may refer to a smaller area or the East C ...

. Some churches decided to send missionaries to convert the Indians. Jason Lee Jason Lee may refer to:

Entertainment

*Jason Lee (actor) (born 1970), American film and TV actor and former professional skateboarder

*Jason Scott Lee (born 1966), Asian American film actor

* Jaxon Lee (Jason Christopher Lee, born 1968), American v ...

, a Methodist

Methodism, also called the Methodist movement, is a group of historically related denominations of Protestant Christianity whose origins, doctrine and practice derive from the life and teachings of John Wesley. George Whitefield and John's b ...

minister from New York, was the first Oregon missionary. He built a mission school for Indians in the Willamette Valley

The Willamette Valley ( ) is a long valley in Oregon, in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States. The Willamette River flows the entire length of the valley and is surrounded by mountains on three sides: the Cascade Range to the east, ...

in 1834. American settlers began to arrive from the east via the Oregon Trail

The Oregon Trail was a east–west, large-wheeled wagon route and Westward Expansion Trails, emigrant trail in the United States that connected the Missouri River to valleys in Oregon. The eastern part of the Oregon Trail spanned part of what ...

starting in the early 1840s and came in increasing numbers each subsequent year. Increased tension led to the Oregon boundary dispute

The Oregon boundary dispute or the Oregon Question was a 19th-century territorial dispute over the political division of the Pacific Northwest of North America between several nations that had competing territorial and commercial aspirations in ...

. Both sides realized that settlers would ultimately decide who controlled the region. The Hudson's Bay Company, which had previously discouraged settlement as it conflicted with the lucrative fur trade, belatedly reversed their position. In 1841, on orders from Sir George Simpson, James Sinclair guided more than 100 settlers from the Red River Colony

The Red River Colony (or Selkirk Settlement), also known as Assiniboia, Assinboia, was a colonization project set up in 1811 by Thomas Douglas, 5th Earl of Selkirk, on of land in British North America. This land was granted to Douglas by the Hud ...

to settle on HBC farms near Fort Vancouver. The Sinclair expedition crossed the Rockies into the Columbia Valley

The Columbia Valley is the name used for a region in the Rocky Mountain Trench near the headwaters of the Columbia River between the town of Golden and the Canal Flats. The main hub of the valley is the town of Invermere. Other towns include Rad ...

, near present-day Radium Hot Springs

Radium Hot Springs, informally and commonly called Radium, is a village of 1,339 residents situated in the East Kootenay region of British Columbia. The village is named for the hot springs located in the nearby Kootenay National Park. From Ban ...

, British Columbia, then traveled southwest down the Kootenai River and Columbia River following the southern portion of the well-established York Factory Express

The York Factory Express, usually called "the Express" and also the Columbia Express and the Communication, was a 19th-century fur brigade operated by the Hudson's Bay Company (HBC). Roughly in length, it was the main overland connection between ...

trade route.

The Canadian effort proved to be too little, too late. In what was dubbed " The Great Migration of 1843" or the "Wagon Train of 1843", an estimated 700 to 1,000 American emigrants came to Oregon, decisively tipping the balance.

Oregon Treaty

James K. Polk

James Knox Polk (November 2, 1795 – June 15, 1849) was the 11th president of the United States, serving from 1845 to 1849. He previously was the 13th speaker of the House of Representatives (1835–1839) and ninth governor of Tennessee (183 ...

supported the 49th parallel as a northern limit for U.S. annexation in Oregon Country. It was Polk's uncompromising support for expansion into Texas and relative silence on the Oregon boundary dispute that led to the phrase "Fifty-Four Forty or Fight!", referring to the northern border of the region and often erroneously attributed to Polk's campaign. The goal of the slogan was to rally Southern expansionists (some of whom wanted to annex only Texas in an effort to tip the balance of slave/free states and territories in favor of slavery) to support the effort to annex Oregon Country, appealing to the popular belief in manifest destiny

Manifest destiny was a cultural belief in the 19th century in the United States, 19th-century United States that American settlers were destined to expand across North America.

There were three basic tenets to the concept:

* The special vir ...

. The British government, meanwhile, sought control of all territory north of the Columbia River.

Despite the posturing, neither country really wanted to fight what would have been the third war in 70 years against the other. The two countries eventually came to a peaceful agreement in the 1846 Oregon Treaty that divided the territory west of the Continental Divide along the 49th parallel to Georgia Strait

The Strait of Georgia (french: Détroit de Géorgie) or the Georgia Strait is an arm of the Salish Sea between Vancouver Island and the extreme southwestern mainland coast of British Columbia, Canada and the extreme northwestern mainland coast ...

; with all of Vancouver Island remaining under British control. This border today divides British Columbia from neighboring Washington, Idaho, and Montana.

Hudson's Bay Company

In 1843 the HBC shifted its Columbia Department headquarters from Fort Vancouver to Fort Victoria on Vancouver Island. The plan to move to more northern locations dated back to the 1820s. George Simpson was the main force behind the move north; John McLoughlin became the main hindrance. McLoughlin had devoted his life's work to the Columbia business, and his personal interests were increasingly linked to the growing settlements in the Willamette Valley. He fought Simpson's proposals to move north in vain. By the time Simpson made the final decision in 1842 to move the headquarters to Vancouver Island, he had had many reasons for doing so. There was a dramatic decline in the fur trade across North America. In contrast the HBC was seeing increasing profits with coastal exports of salmon and lumber to Pacific markets such asHawaii

Hawaii ( ; haw, Hawaii or ) is a state in the Western United States, located in the Pacific Ocean about from the U.S. mainland. It is the only U.S. state outside North America, the only state that is an archipelago, and the only stat ...

. Coal deposits on Vancouver Island had been discovered, and steamships such as the ''Beaver

Beavers are large, semiaquatic rodents in the genus ''Castor'' native to the temperate Northern Hemisphere. There are two extant species: the North American beaver (''Castor canadensis'') and the Eurasian beaver (''C. fiber''). Beavers ar ...

'' had shown the growing value of coal, economically and strategically. A general HBC shift toward Pacific shipping and away from the interior of the continent made Victoria Harbour

Victoria Harbour is a natural landform harbour in Hong Kong separating Hong Kong Island in the south from the Kowloon Peninsula to the north. The harbour's deep, sheltered waters and strategic location on South China Sea were instrumental i ...

much more suitable than Fort Vancouver's location on the Columbia River. The Columbia Bar

The Columbia Bar, also frequently called the Graveyard of the Pacific, is a system of bar (landform), bars and shoals at the mouth of the Columbia River spanning the U.S. states of Oregon and Washington (state), Washington. It is known as one of th ...

at the river's mouth was dangerous and routinely meant weeks or months of waiting for ships to cross. The largest ships could not enter the river at all. The growing numbers of American settlers along the lower Columbia gave Simpson reason to question the long term security of Fort Vancouver. He worried, rightfully so, that the final border resolution would not follow the Columbia River. By 1842, he thought it more likely that the United States would at least demand Puget Sound

Puget Sound ( ) is a sound of the Pacific Northwest, an inlet of the Pacific Ocean, and part of the Salish Sea. It is located along the northwestern coast of the U.S. state of Washington. It is a complex estuarine system of interconnected ma ...

, and the British government would accept a border as far north as the 49th parallel, excluding Vancouver Island. Despite McLoughlin's stalling, the HBC had begun the process of shifting away from Fort Vancouver and toward Vancouver Island and the northern coast in the 1830s. The increasing number of American settlers arriving in the Willamette Valley after 1840 served to make the need more pressing.

Oregon Territory

In 1848, the U.S. portion of the Oregon Country was formally organized as the Oregon Territory. In 1849, Vancouver Island became a BritishCrown colony

A Crown colony or royal colony was a colony administered by The Crown within the British Empire. There was usually a Governor, appointed by the British monarch on the advice of the UK Government, with or without the assistance of a local Counci ...

—the Colony of Vancouver Island

The Colony of Vancouver Island, officially known as the Island of Vancouver and its Dependencies, was a Crown colony of British North America from 1849 to 1866, after which it was united with the mainland to form the Colony of British Columbia ...

—with the mainland being organized into the Colony of British Columbia The Colony of British Columbia refers to one of two colonies of British North America, located on the Pacific coast of modern-day Canada:

*Colony of British Columbia (1858–1866)

*Colony of British Columbia (1866–1871)

See also

*History of Br ...

in 1858. Shortly after the establishment of Oregon Territory, there was an effort to split off the region north of the Columbia River. As a result of the Monticello Convention

The Monticello Convention refers to a set of two separate meetings held in 1851 and 1852 to petition Congress to split the Oregon Territory into two separate territories; one north of the Columbia River and one south.

Background

The influx of pe ...

, Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of a ...

approved the creation of Washington Territory

The Territory of Washington was an organized incorporated territory of the United States that existed from March 2, 1853, until November 11, 1889, when the territory was admitted to the Union as the State of Washington. It was created from the ...

in early 1853. President

President most commonly refers to:

*President (corporate title)

*President (education), a leader of a college or university

*President (government title)

President may also refer to:

Automobiles

* Nissan President, a 1966–2010 Japanese ful ...

Millard Fillmore

Millard Fillmore (January 7, 1800March 8, 1874) was the 13th president of the United States, serving from 1850 to 1853; he was the last to be a member of the Whig Party while in the White House. A former member of the U.S. House of Represen ...

approved the new territory on 2 March 1853.

Descriptions of the land and settlers

Alexander Ross, an early Scottish Canadian fur trader, describes the lower Columbia River area of the Oregon Country (known to him as the Columbia District): After living in Oregon from 1843 to 1848,Peter H. Burnett

Peter Hardeman Burnett (November 15, 1807May 17, 1895) was an American politician who served as the first elected California interim government, 1846–1850#Interim governors, Governor of California from December 20, 1849, to January 9, 1851. Bur ...

wrote:

See also

*American frontier

The American frontier, also known as the Old West or the Wild West, encompasses the geography, history, folklore, and culture associated with the forward wave of United States territorial acquisitions, American expansion in mainland North Amer ...

* Bibliography of Oregon history

For a useful starting point goto Oregon Encyclopedia of History and Culture (2022). Not yet in print format; it isonline here with 2000 articles.

The following published works deal with the cultural, political, economic, military, biographica ...

* Canada–United States border

The border between Canada and the United States is the longest international border in the world. The terrestrial boundary (including boundaries in the Great Lakes, Atlantic, and Pacific coasts) is long. The land border has two sections: Can ...

* American Imperialism

American imperialism refers to the expansion of American political, economic, cultural, and media influence beyond the boundaries of the United States. Depending on the commentator, it may include imperialism through outright military conques ...

* Cascadia (independence movement), a contemporary movement to make the Cascadian bioregion, roughly covering the same area as the Oregon country, an independent country

* New Albion

New Albion, also known as ''Nova Albion'' (in reference to an archaic name for Britain), was the name of the continental area north of Mexico claimed by Sir Francis Drake for England when he landed on the North American west coast in 1579. Thi ...

* Robert Gray's Columbia River expedition

In May 1792, American merchant sea captain Robert Gray sailed into the Columbia River, becoming the first recorded American to navigate into it. The voyage, conducted on the privately owned , was eventually used as a basis for the United Stat ...

* Royal Proclamation of 1763

The Royal Proclamation of 1763 was issued by King George III on 7 October 1763. It followed the Treaty of Paris (1763), which formally ended the Seven Years' War and transferred French territory in North America to Great Britain. The Procla ...

– another British-border treaty dependent on one or more hydrology divides to determine at least one of its borders

* Russo-American Treaty of 1824

The Russo-American Treaty of 1824 (also known as the Convention of 1824) was signed in St. Petersburg between representatives of Russia and the United States on April 17, 1824, ratified by both nations on January 11, 1825 and went into effect on J ...

* Treaty of Saint Petersburg (1825)

The Treaty of Saint Petersburg of 1825 or the Anglo-Russian Convention of 1825, officially the Convention Concerning the Limits of Their Respective Possessions on the Northwest Coast of America and the Navigation of the Pacific Ocean, defined th ...

References

Bibliography

* Richard W. Etulain, ''Lincoln and Oregon Country Politics in the Civil War.'' Corvallis, OR: Oregon State University Press, 2013.External links

Chronology of Oregon Events

(Treaty of St. Petersburg, 1825) {{Coord, 48, -122, region:US-OR_dim:1800000, display=title

Country

A country is a distinct part of the world, such as a state, nation, or other political entity. It may be a sovereign state or make up one part of a larger state. For example, the country of Japan is an independent, sovereign state, while the ...

Pre-Confederation British Columbia

History of the American West